A report from a conflict zone the world ignores

ALONG the road from the port city of Hodeida to Sana’a, Yemen’s capital, rugged mountains rise sharply from a coastal plain, then level off, giving way to a raised plateau. Old stone farmhouses overlook terraced fields, fed by mountain rains. To the south are lush forests, where baboons and wildcats live. Yemen’s vast deserts spread to the east. The diversity of the landscape is breathtaking. But amid all this natural beauty, there is misery.

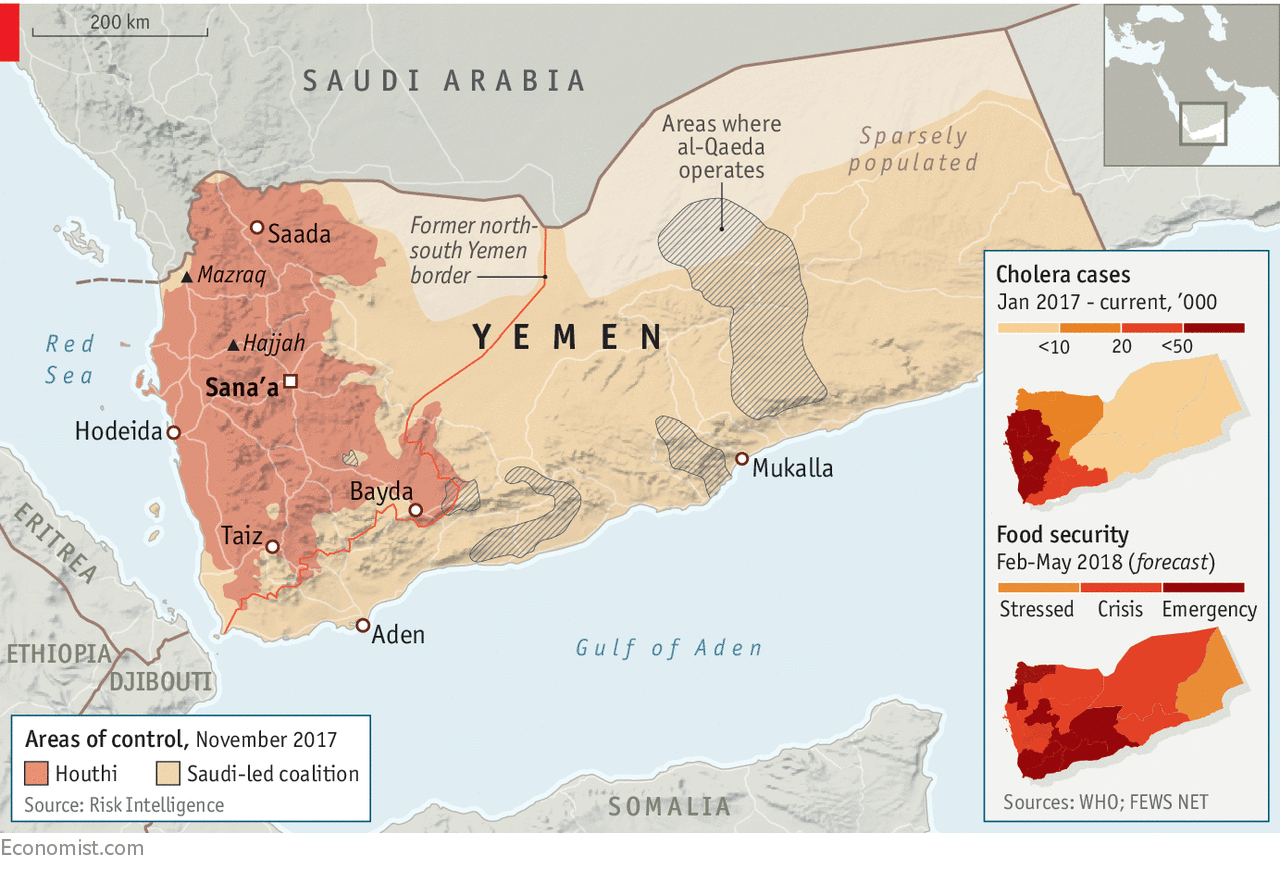

Yemen was the poorest country in the Middle East even before the outbreak of war in 2014 between Houthi rebels and government forces. The conflict has heaped devastation upon poverty. Since fighting began Yemen has suffered the biggest cholera outbreak in modern history and is on the brink of the harshest famine the world has seen for decades. The conflict has shattered the water, education and health systems. The UN says that it is the world’s worst current humanitarian crisis. Three-quarters of the population of 28m need help.

The war in Yemen, and looming humanitarian catastrophe, has gone largely unnoticed beyond its borders. The fighting is rooted in old conflicts and now involves many groups, sucking in Yemen’s neighbours. But no single force has emerged that is strong enough or competent enough to hold the entire country together, making the prospects for peace dim.

Yemen’s infrastructure has been crumbling for years, so it is difficult for a visitor to tell between buildings that are falling down through neglect and those half-levelled by explosions. But locals point out the damage wrought by a bombing campaign led by Saudi Arabia, part of an international coalition that supports the government. Although American and British military advisers have helped the Saudis to choose targets, and their governments have provided them with precision-guided munitions, or “smart bombs”, the air strikes often seem to miss their mark.

The Houthis, a group of Shia rebels, are the main target. Unhappy with reforms to the state and their share of power, they swept out of their northern stronghold in 2014 and overran Sana’a. With the support of Iran and the forces of a former dictator, Ali Abdullah Saleh, the Houthis then moved south, taking control of most of the rest of Yemen. The president, Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi, fled—first to Aden, a southern port, then to Saudi Arabia, where he remains. At his request, the Saudis stepped in and, with local forces, pushed back the Houthis to the north of the country.

Coalition air strikes have targeted factories and food-storage warehouses, as well as the airport in Sana’a. The road from the capital to Hodeida is pockmarked with craters. At the port, the cranes used to unload ships have been put out of action. Once the lifeline of the north, it now operates at well under its former capacity. For months America tried to supply new cranes, but they were turned back by Gulf members of the coalition.

Ships and planes carrying food, fuel and medicine are monitored by the UN to ensure that arms are not entering the north. But the coalition still holds up shipments. In November it cut off northern ports completely for over two weeks. Even the more limited blockade has created a cycle of suffering. A lack of fuel has crippled water-pumping stations, so locals have resorted to drinking from dirty sources. Cholera is often the result. The medicine to treat it is also held up by the coalition.

Nowhere is safe

Nothing seems out of bounds for the bombers. About 40 health centres were struck by the coalition over the first six months of the war. Amnesty International, a pressure group, has accused it of deliberately targeting civilians, hospitals, schools, markets and mosques; and of using imprecise weapons, such as cluster bombs, which most countries have outlawed. A spokesman for the coalition once declared the entire city of Saada, home to about 50,000 people, a military target.

That is where Ali Marhad (see picture) lived before fighting about a decade ago forced him to flee. He moved into a camp for displaced people in Mazraq. But it was bombed in 2015 by the coalition, killing 40 people, including his two sons, he says. He then moved to a camp in Hajjah. Earlier this year another bomb fell near his home, a collection of sticks and tarpaulin. It is exceedingly difficult for ordinary Yemenis to escape the fighting.

At least 10,000 people, most of them civilians, have been killed by bullets and bombs. Around 40 times more people have died in Syria’s war, which also sent a wave of refugees to Europe. Perhaps that is why it has gained international attention, while the conflict in Yemen is overlooked. Less than half of the British public is aware of it. The death toll is anyway misleading. Many more Yemenis have died from a lack of food and medicine than from the fighting, of which the shortages are a direct result. The war continues, though the front line has hardly budged in the past year.

Fighting is not unusual in Yemen. Sitting at the south-western tip of the Arabian peninsula, on important trade routes, the land has long been coveted by foreign powers. In the past century it has seen about a dozen conflicts, involving over half a dozen countries.

Some seeds of today’s fighting were sown in battles in the 1960s—a civil war in the north and an insurgency against British colonial forces in the south. Two distinct Yemeni states arose. Leaders in the north turned to religious authority for their legitimacy, enlisting the support of Islamic clerics. The more secular south adopted Marxism and aligned itself with the Soviet Union. Political feuding led to further wars in 1972 and 1979, but economic hardship and the end of the cold war brought the sides together. After a series of failed agreements in the 1970s and 1980s, north and south at last agreed on a new constitution in 1990, in the hope that a show of unity would attract foreign investment and increase the extraction of Yemen’s oil.

Money briefly flowed in and oil out. But simmering ill-feeling erupted into civil war in 1994 in which Mr Saleh’s northern forces were victorious. In the aftermath his General People’s Congress (GPC) dominated parliament, then set about consolidating power. Parliamentary elections in 2003 were postponed and critics detained. Mr Saleh and his henchmen are thought to have stolen billions of dollars of state funds, while most Yemenis got by on less than $3 a day. Resentment of his rule grew.

The Zaydis, a Shia sect, who make up perhaps 40% of the population, felt particularly marginalised by Mr Saleh (though he is one of them). The Houthis emerged from this group in the 1990s, bristling at the growth of the Saudis’ conservative religious influence and Yemen’s alliance with America in its war on terror. Mr Saleh, in turn, accused the group of wanting to overthrow his government. Hundreds of people died in fighting between the Houthis and pro-government forces between 2004 and 2010—including Hussein Badruddin al-Houthi, the group’s leader, from whom it takes its name.

Opposition to Mr Saleh’s rule came to a head during the Arab spring of 2011, when tens of thousands of Yemenis took to the streets. With a push from the Gulf states, he stepped down in 2012 and was succeeded by Mr Hadi, his vice-president. Thus began a short-lived period of hope. Talks overseen by the UN led to a plan in 2014 for a new constitution enshrining a federal system and a parliament split between northerners and southerners.

The Houthis, however, continued to distrust the government. They boycotted an election won by Mr Hadi in 2012 and opposed the agreement of 2014, on the grounds that it stuck most of them in a region with few resources and no access to the sea. Nor had they received positions in the government that they wanted. Their frustration was shared by Mr Saleh, who sought to undermine the transition in the hope of regaining the presidency or, at least, handing it to his son.

Resentment towards Mr Hadi and disquiet over the growing power of Islah, an Islamist party affiliated to the Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt’s main Islamist group, brought the Houthis and Mr Saleh into an unlikely alliance in 2014. In September of that year their forces entered Sana’a—and were welcomed by many Yemenis who had become disenchanted with Mr Hadi’s ineffective leadership. A power-sharing deal between the Houthis and the government was brokered by the UN—and then ignored. In early 2015 the rebels seized full control of the capital. By March they had made it to Aden.

Muhammad fears a Houthi

But it was also becoming clear that the Houthis, motivated by grievances, did not have a plan for ruling Yemen. In areas under their control, rubbish is piling up, cash is hard to get hold of and the lights have gone out. “My sense of it is that they never really had a clear political agenda, both during the wars with Saleh and after,” says April Longley Alley of the International Crisis Group, a think-tank.

The incompetence of the Houthis has been compounded by the involvement of Saudi Arabia. Saudi meddling in Yemen is nothing new. In 1934 Saudi soldiers retook towns seized by the Zaydis. Prince Saud, their leader, would later become king. Today Prince Muhammad bin Salman is first in line to the throne. But his adventure in Yemen, which seemed designed to build him a reputation as a strong leader, has led Saudi Arabia into a quagmire.

Responding to Mr Hadi’s call for help, Prince Muhammad organised a coalition that included Egypt, Morocco, Jordan, Sudan, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Bahrain. They began striking Yemen from the air and the sea in March 2015. A month later the Saudis declared the air campaign over. It had “achieved its military goals”, officials said. A new operation would supposedly focus on finding a political solution in Yemen.

In reality, the war was just beginning. Over the next months, local forces backed by coalition air strikes (and later soldiers) pushed the Houthis back. However, they have not been able to drive them out of territory seized in the north, including Sana’a. So instead the coalition seems intent on starving the north.

The Saudis have created much of the misery that blights Yemen, but blame falls on others, too. The Houthis and Mr Saleh’s forces have also carried out indiscriminate attacks in cities such as Taiz and Aden. They have held up aid and are accused of war profiteering. Mr Hadi says the Houthis looted around $4bn from the central bank to pay for the war (the Houthis say the money was used for food and medicine). So he moved the bank from Sana’a to Aden in 2016 and stopped paying the salaries of public servants in the north. Schools and hospitals have closed and many northerners face destitution.

For Saudi Arabia, the region’s Sunni champion, the failure of its campaign in Yemen is twofold. Not only was it designed to reinstate Mr Hadi’s government—it was also supposed to send a signal to Iran’s Shia regime. The two powers are locked in a struggle for regional dominance that has spilled over into Syria, Lebanon and Iraq. The Saudis fear that, in the Houthis, Iran is nurturing a Shia proxy, akin to Hizbullah, the Lebanese militia that it backs. Yet again Yemen is the playground of bigger powers.

America has concluded that Iran does not exert “command and control” over the Houthis. But there is little doubt that it is arming the group. It appears to have supplied missiles the Houthis have fired. America’s most senior admiral in the region told the New York Times in September that Iran is providing anti-ship and ballistic missiles, mines and exploding boats that the rebels have used to attack coalition ships in the Red Sea. When the Saudis shot down a missile fired from Yemen on its way to Riyadh on November 4th, they called it an “act of war” by Iran.

The possibility that the war might end soon is slender. The Saudis have powerful backing to continue their fight. President Donald Trump has nothing but praise for them. When he visited Riyadh in May he applauded their “strong action” against the Houthis and agreed to sell them $110bn worth of “beautiful” arms. The war has also been a blessing for Britain’s defence industry, which has hugely increased sales of missiles and bombs to Saudi Arabia since the start of the war. As the European Parliament approved a non-binding arms embargo against the Saudis in 2016, David Cameron, then the prime minister, sounded almost Trumpian, praising the “brilliant” weapons that Britain was selling to the kingdom. His successor, Theresa May, at least expressed her concerns over the war.

America and Britain not only support Saudi Arabia but have blocked other countries from putting pressure on it. Along with France, which also sells weapons to the Saudis, they undercut a UN resolution in 2015 that would have set up a panel to examine abuses in the war. When urging the creation of a new panel earlier this year, Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein, the UN high commissioner for human rights, condemned “the reticence of the international community in demanding justice for the victims of the conflict”. The panel was approved—but only after America, Britain and France had watered it down.

The UN has organised three rounds of peace talks. But Mr Hadi’s government insists that the Houthis lay down their arms and withdraw from the areas they have seized. The Houthis complain that they are the only group that UN resolutions ask to give ground. In May a convoy led by Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed, the UN envoy to Yemen, was attacked by demonstrators in Sana’a. “There will be no more contact with [him] and he is not welcome here,” said Saleh al-Samad, a Houthi leader, a month later.

As the war drags on, both sides appear unsteady. In the south the Saudis along with the Emiratis, who are the largest foreign force on the ground, have built an unwieldy alliance of Salafists, southern secessionists and other militias. “Whatever Gulf money can buy,” says an observer. Some of these groups are accused of working with jihadists, such as al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, though the Emiratis have pushed back al-Qaeda. No one thinks Mr Hadi has a long-term future.

North-south divides

In the north the Houthis accuse Mr Saleh of negotiating secretly with the coalition (though they have done the same). Mr Saleh, who is the weaker partner, fears being left out of any settlement. Things came to a head in August, when clashes between Houthis and supporters of Mr Saleh led to deaths on both sides. They have since made up but tension remains high. And there is a split within the Houthis, between hardliners and moderates. The group’s leader, Abdel-Malik al-Houthi, is seen as willing to negotiate. However, analysts say that, the longer the war goes on, the stronger the hardliners become.

Some spy an opening. Ms Alley reckons that the divisions, as long as they do not develop into open conflict, are an opportunity for some kind of deal. “Carrots have to be offered to those willing to compromise—right now it is all sticks,” she says. Yet the Saudis, under little pressure from abroad, do not look like backing down and seem to hope that the population in the north will rise up against the Houthis. Frustration with Houthi rule is growing, something Mr Saleh seems keen to exploit, but so far the streets are mostly quiet.

Others may not want peace. Warlords profit from extortion or by selling looted aid on the black market. Mr Hadi’s government and other combatants are accused of creating shortages so that they can sell items, such as fuel, at a big mark-up. Even if the Saudis were to withdraw, many analysts think that the fighting within Yemen would continue—between northerners and southerners, the Houthis and Mr Saleh or Islah and any number of parties.

Ordinary Yemenis are less interested in such divisions. A crowd gathers around Ali Marhad’s tent as he dispassionately recounts his hardship. They come from Houthi territory, but they say they have no tribe, no money, no home, “just Allah”. Do they care who wins the war? “No!” they cry. They just want it to end.

Leave A Comment